马六甲 之 峇峇娘惹

This short explanation notes, is only presented for educational purposes, as a reference for visitors and public to understand one of our unique cultural community in Melaka - Nyonya Baba World!

We welcome more comments and feedback from Blog’s visitors, friends of our Museum, any cultural interesting individual and parties to help us to update this non profit e-Library of our Group.

Attached photos taken are part of our Nyonya Baba’s cultural corridor, Nyonya Baba-oriented architectural designed historic buildings, are strategically laid along the Tun Tan Cheng Lock ( also known as Hereen Street ) , next to Jonker Street ( Jalan Hang Jebat ) where Jonker88 are serving their Nyonya-based & Baba-related drinks and traditional food, like Nyonya Asam Laksa, Baba Cendul, Baba Laksa, Goereng2, Nyonya Salad, Rendang, Nasi Lemak, Ah Mah hand-made fresh fish cakes, fish ball and homely made fish products…..

Peranakan Chinese and Baba-Nyonya are terms used for the descendants of late 15th and 16th-century Chinese immigrants to the Indonesian archipelago and British Malaya (now Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore).

Members of this community in Melaka, Malaysia address themselves as "Nyonya Baba". Nyonya is the term for the women and Baba for the men.

The beginning....

峇峇娘惹(拼音:Bābā Niángrě),或稱土生華人(马来语:Baba Nyonya)是指十五世纪初期定居在满剌伽(马六甲)、满者伯夷国和室利佛逝国(印尼)和淡马锡(新加坡)一带的中國明朝移民后裔。

峇峇娘惹也包括少数在唐宋时期定居此地的唐人,但目前没有来源证明唐宋已有唐人定居此地,所以一般上峇峇娘惹都是指明朝移民后裔。

這些唐宋明后裔的文化在一定程度上受到当地馬來人或其他非華人族群的影響。男性称为峇峇,女性称为娘惹。

六十年代以前峇峇娘惹在馬來西亞是土著身份(Bumiputra),但由于某些政党政治因素而被馬來西亞政府归类为華人(也就是馬來西亞華人),从此失去了土著身份。峇峇娘惹今天在馬來西亞宪法上的身份和十九世纪后期来的“新客”无分别。

這些峇峇人,主要是在中国明朝或以前移民到东南亚,大部分的原籍是中国福建或广东潮州地区,小部分是广府和客家籍,很多都与马来人混血。

某些峇峇文化具有中国传统文化色彩,例如他们的传统婚礼是以中國傳統儀式為主,服飾(尤其是女裝)則是從明代的漢服演變而來的可巴雅。

峇峇人講的語言稱為峇峇話,並非單純的福建話,在使用漢語語法的同时,依地區不同,參雜使用馬來語与泰語詞彙的比例也隨之不同。

有些受華文教育的华人也稱那些從小受英式教育的華人為“峇峇”,這個用法有藐視的意思,表示此華人已经数典忘祖或者不太像華人了。此外,當地的閩南人亦有句成語叫作‘三代成峇’,根據這句话的定義,所有在馬來西亞出生的第三代華人也都成了峇峇,但這句话沒有藐視的成份,只是意味到了第三代華人,由於適應當地的社會環境的緣故,其文化難免帶有當地色彩。

此外,峇峇亦特指一個自稱並被稱为“峇峇”的華人族群,也就是今日在馬六甲以及馬來西亞獨立前在檳城和新加坡的峇峇,峇峇華人講馬來語,他們也自稱為“Peranakan”——馬來語中“土生的人”,故“Cina Peranakan”即土生華人,這一詞本用來識別“峇峇人”與“新客”——也就是清末以来從中國來的移民。

在19世紀的馬來半島,這樣的分別很明顯也很重要,“峇峇”是土生的,而“新客”是移民,兩者的生活習慣和政治意識不太一樣。

虽然現在的馬來西亞華人大都是本地出生的,可是“Peranakan”一詞已成為“峇峇人”的专用自稱。

在今天的马来西亚,一位马来西亚华人男子如取一位马来女子为妻,他自己也要皈依伊斯蘭教,取穆斯林名字,他们的子女也不是峇峇娘惹,是混血儿。峇峇娘惹可谓当世产生的特殊族群。

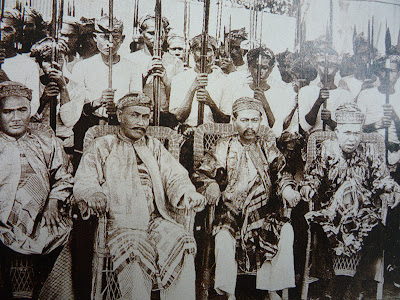

英殖民地时代

由于英国殖民统治马来亚,故当年大多数土生华人接受英语教育,懂得三种语言能够同时接触中国人,马来人和英国人,也因为他们懂得三种语言的缘故,在英政府统治期间有大部分土生华人从事国家行政和公务员职位。

由于长期和英国人交往,有很多土生华人皈依基督教。渐渐地土生华人也就成为了海峡殖民地(槟城,马六甲和新加坡)有影响力的一个团体,并也被称为“King's Chinese ” (国王的华人)同时也效忠英女王。

由于土生华人“土生土长”的身份又受到英政府的重用,生活基本上已经属于富裕,故把后期到来的华人和华工区分为新客。

文化認同

一般具有較強烈中华意識的人士经常批評峇峇娘惹「数典忘祖」,然而馬來西亞華人公會的創始人陳禎祿本身是诞生于马六甲的土生峇峇华人,但他也曾經有如下想法:

“华人若不爱护华人的文化,英人不会承认他是英人,巫人也不会承认他是巫人,结果,他将成为无祖籍的人,世界上只有猪牛鸡鸭这些畜生禽兽是无所谓祖籍的,所以,华人不爱护华人文化,便是畜生禽兽”。

“失掉自己文化熏陶的华人,绝对不会变得更文明。一个人的母语,就像一个人的影子,不能够和他本身分离。”

陳禎祿逝 世后,他的墓碑上刻着“民国四十九/庚子年十月二十五日仙逝”。当时距离英国承认中华人民共和国和中华民国迁台已经十年之久,加上马来西亚已于1957年 独立,马来西亚华人普遍上为了避免其他种族质疑效忠程度已采用西元纪年。

陈氏家族采用民国纪年为正朔,也證實峇峇在某種程度上仍然具有中華意識。

马六甲三保山墓地达二十五公顷,有一万两千个坟墓,许多墓碑就是明、清、民国三代遗存的。其中一块墓碑以明朝为正朔刻了“皇明显考维弘黄公妣寿姐谢氏墓。

壬戌年仲冬谷旦、孝男黄子、辰同立”,这一墓碑受不少学者在马六甲研究上引用。

对于中國籍先祖留下来的礼仪, 马六甲峇峇娘惹社群虽不懂涵义却保留下来,让三保山成为中華風格濃厚的地方。

Total population

|

8,000,000 (estimates)

|

Regions with significant populations

|

Languages

|

Religion

|

Related ethnic groups

|

It applies especially to the ethnic Chinese populations of the British Straits Settlements of Malaya and the Dutch-controlled island of Java and other locations, who have adopted to Nusantara customs — partially or in full — to be somewhat assimilated into the local communities.

Many were the elites of Singapore, more loyal to the British than to China.

Most have lived for generations along the straits of Malacca and most have a lineage where intermarriage with the local Indonesians and Malays have taken place.

They were usually traders, the middleman of the British and the Chinese, or the Chinese and Malays, or vice versa because they were mostly English educated.

Because of this, they almost always had the ability to speak two or more languages. In later generations, some lost the ability to speak Chinese as they became assimilated to the Malay Peninsula's culture and started to speak Malay fluently as a first or second language.

While the term Peranakan is most commonly used among the ethnic Chinese for those of Chinese descent also known as Straits Chinese (土生華人; named after the Straits Settlements)There are also other, comparatively small Peranakan communities, such as Indian Hindu Peranakans (Chitty), Indian Muslim Peranakans (Jawi Pekan) (Jawi being the Javanised Arabic script, Pekan a colloquial contraction of Peranakan and Eurasian Peranakans (Kristang) (Kristang = Christians)

The group has parallels to the Cambodian Hokkien, who are descendants of Hoklo Chinese. They maintained their culture partially despite their native language gradually disappearing a few generations after settlement.

Most Peranakans are of Hoklo (Hokkien) ancestry, although a sizable number are of Teochew or Cantonese descent. Originally, the Peranakan were mixed-race descendants, part Chinese, part Malay/Indonesian.

Baba Nyonya are a subgroup within Chinese communities, are the descendants of Sino-indigenous unions in Melaka, Penang, and Indonesia.

It was not uncommon for early Chinese traders to take Malay/Indonesian women of Peninsular Malay/Sumatera/Javanese as wives or concubines Consequently the Baba Nyonya possessed a mix of cultural traits.

Written records from the 19th and early 20th centuries show that Peranakan men usually took brides from within the local Peranakan community. Peranakan families occasionally imported brides from China and sent their daughters to China to find husbands.

Some sources claim that the early Peranakan inter-married with the local Malay/Indonesian population; this might derive from the fact that some of the servants who settled in Bukit Cina who traveled to Malacca with the Admiral from Yunnan were Muslim Chinese.

Other experts, however, see a general lack of physical resemblance, leading them to believe that the Peranakan Chinese ethnicity has hardly been diluted.

One notable case to back the claim is of the Peranakan community in Tangerang, Indonesia, known as Cina Benteng. Their physical look is indigenous, yet they dutifully adhere to the Peranakan customs, and most of them are Buddhist.

Some Peranakan distinguish between Peranakan-Baba (those Peranakan with part Malay ancestry) from Peranakan (those without any Malay ancestry).

The language of the Peranakans, Baba Malay (Bahasa Melayu Baba), is a creole dialect of the Malay language (Bahasa Melayu), which contains many Hokkien words.

It is a dying language, and its contemporary use is mainly limited to members of the older generation. English has now replaced this as the main language spoken amongst the younger generation.

In Indonesia, young Peranakans can still speak this creole language, although its use is limited to informal occasions.

Young Peranakans have lost much of their traditional language, so there is normally a difference in vocabulary between the older and younger generations.

In the 15th century, some small city-states of the Malay Peninsula often paid tribute to various kingdoms such as those of China and Siam.

Close relations with China were established in the early 15th century during the reign of Parameswara when Admiral Zheng He (Cheng Ho), a Muslim Chinese, visited Malacca and Java.

According to a legend in 1459 CE, the Emperor of China sent a princess, Hang Li Po, to the Sultan of Malacca as a token of appreciation for his tribute.

The nobles (500 sons of ministers) and servants who accompanied the princess initially settled in Bukit Cina and eventually grew into a class of Straits-born Chinese known as the Peranakans.

Due to economic hardships at mainland China, waves of immigrants from China settled in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore.

Some of them embraced the local customs, while still retaining some degree of their ancestral culture; they are known as the Peranakans. Peranakans normally have a certain degree of indigenous blood, which can be attributed to the fact that during imperial China, most immigrants were men who married local women.

Peranakans at Tangerang, Indonesia, held such a high degree of indigenous blood that they are almost physically indistinguishable from the local population. Peranakans at Indonesia can vary between very fair to copper tan in color.

Chinese men in Melaka fathered children with Javanese, Batak and Balinese slave women. Their descendants moved to Penang and Singapore during British rule.

Chinese men in colonial southeast Asia also obtained slave wives from Nias. Chinese men in Singapore and Penang were supplied with slave wives of Bugis, Batak, and Balinese origin.

The British tolerated the importation of slave wives since they improved the standard of living for the slaves and provided contentment to the male population. The usage of slave women as wives by the Chinese was widespread.

It cannot be denied, however, that the existence of slavery in this quarter, in former years, was of immense advantage in procuring a female population for Pinang.

From Assaban alone, there used to be sometimes 300 slaves, principally females, exported to Malacca and Pinang in a year. The women get comfortably settled as the wives of opulent Chinese merchants, and live in the greatest comfort.

Their families attach these men to the soil; and many never think of returning to their native country. The female population of Pinang is still far from being upon a par with the male; and the abolition therefore of slavery, has been a vast sacrifice to philanthropy and humanity.

As the condition of the slaves who were brought to the British settlements, was materially improved, and as they contributed so much to the happiness of the male population, and the general prosperity of the settlement, I am disposed to think (although I detest the principles of slavery as much as any man), that the continuance of the system here could not, under the benevolent regulations which were in force to prevent abuse, have been productive of much evil.

The sort of slavery indeed which existed in the British settlements in this quarter, had nothing but the name against it; for the condition of the slaves who were brought from the adjoining countries, was always ameliorated by the change; they were well fed and clothed; the women became wives of respectable Chinese; and the men who were in the least industrious, easily emancipated themselves, and many became wealthy.

Severity by masters was punished; and, in short, I do not know any race of people who were, and had every reason to be, so happy and contented as the slaves formerly, and debtors as they are now called, who came from the east coast of Sumatra and other places.

John Anderson - Agent to the Government of Prince of Wales Island

Peranakans themselves later on migrated between Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore, which resulted in a high degree of cultural similarity between Peranakans in those countries.

Economic / educational reasons normally propel the migration between of Peranakans between the Nusantara region (Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore), their creole language is very close to the indigenous languages of those countries, which makes adaptations a lot easier.

For political reasons Peranakans and other Nusantara Chinese are grouped as a one racial group, Chinese, with Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia becoming more adoptive of mainland Chinese culture, and Chinese in Indonesia becoming more diluted in their Chinese culture.

Such things can be attributed to the policies of Bumiputera and Chinese-National Schools (Malaysia), mother tongue policy (Singapore) and the ban of Chinese culture during the Soeharto era in Indonesia.

In old times the Peranakans were held in high regard by Malays. Some Malays in the past may have taken the word "Baba", referring to Chinese males, and put it into their name, when this used to be the case.

This is not followed by the younger generation, and the current Chinese Malaysians do not have the same status or respect as Peranakans used to have.

Political affinity

Baba Nyonya were financially better off than China-born Chinese. Their family wealth and connections enabled them to form a Straits-Chinese elite, whose loyalty was strictly to Britain or the Netherlands.

Due to their strict loyalty, they did not support Malaysian nor Indonesian Independence

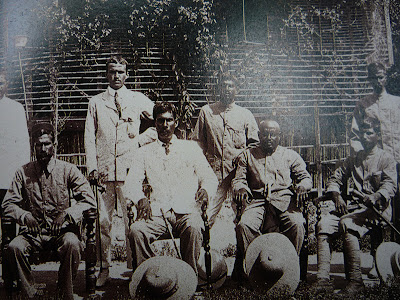

By the middle of the twentieth century, most Peranakan were English or Dutch-educated, as a result of the Western colonization of Malaya and Indonesia, Peranakans readily embraced English culture and education as a means to advance economically thus administrative and civil service posts were often filled by prominent Straits Chinese.

Many in the community chose to convert to Christianity due to its perceived prestige and proximity to the preferred company of British and Dutch.

The Peranakan community thereby became very influential in Malacca and Singapore and were known also as the King's Chinese due to their loyalty to the British Crown.

Because of their interaction with different cultures and languages, most Peranakans were (and still are) trilingual, being able to converse in Chinese, Malay, and English.

Common vocations were as merchants, traders, and general intermediaries between China, Malaya and the West; the latter were especially valued by the British and Dutch.

Things started to change in the first half of the 20th century, with some Peranakans starting to support Malaysian and Indonesian independence. In Indonesia three Chinese communities started to merge and become active in the political scene.

They were also among the pioneers of Indonesian newspapers. In their fledgling publishing companies, they published their own political ideas along with contributions from other Indonesian writers.

In November 1928, the Chinese weekly Sin Po (traditional Chinese: 新報; pinyin: xīn bào) was the first paper to openly publish the text of the national anthem Indonesia Raya.

On occasion, those involved in such activities ran a concrete risk of imprisonment or even of their lives, as the Dutch colonial authorities banned nationalistic publications and activities.

Sponsored by

MAM Jonker88 Group,

International Cultural Exchange Foundation

No comments:

Post a Comment